About this resource

This page provides the Year 0-6 part of the English learning area of the New Zealand Curriculum, the official document that sets the direction for teaching, learning, and assessment in all English medium state and state-integrated schools in New Zealand. In English, students study, use, and enjoy language and literature communicated orally, visually, or in writing. It comes into effect on 1 January 2025. The Year 7 to 13 content is provided on a companion page.

We have also provided the English Year 0-6 curriculum in PDF format. There are different versions available for printing (single page), viewing online (spreads), and to view by phase. You can access these using the icons below. Use your mouse and hover over each icon to see the document description.

File Downloads

No files available for download.

Links to English supports and resources:

The following material on the New Zealand Curriculum, whakapapa of Te Mātaiaho and overview of the learning areas provides context when using the English Year 0-6 Learning Area. It is not part of the statement of official policy.

Te Mātaiaho | The New Zealand Curriculum English – Years 0‑6 (statement of official government policy) |

Ko te reo tōku tuakiri, ko te reo tōku ahurei, ko te reo te ora. |

Board requirements

English Years 0–6 is published by the Minister of Education under section 90(1) of the Education and Training Act 2020 (the Act) as a foundation curriculum policy statement and a national curriculum statement. These are the statements of official policy in relation to the teaching of English (including literacy) that give direction to each school’s curriculum and assessment responsibilities (section 127 of the Act), teaching and learning programmes (section 164 of the Act), and monitoring and reporting of student performance (section 165 of the Act and associated Regulations). School boards must ensure that they and their principal and staff give effect to these statements. The sections of English Years 0–6 that are published as a national curriculum statement are the Understand–Know–Do (UKD) progress outcomes for each phase (UKD for phase 1 and UKD for phase 2). These set out what students are expected to learn over their time at school, including the desirable levels of knowledge, understanding, and skill to be achieved in English. The rest is published as a foundation curriculum policy statement. This sets out expectations for teaching, learning, and assessment that underpin the national curriculum statement and give direction for effective English (including literacy / reading and writing) teaching and learning programmes. The statements come into effect on 1 January 2025. They replace curriculum levels 1–3 of the existing English national curriculum statement (learning area). The remainder of the existing English national curriculum statement remains in force. Apart from those for Mathematics and statistics Years 0–8, other existing foundation curriculum policy statements and national curriculum statements for the New Zealand Curriculum remain in place. Schools should choose the appropriate English statements for their students’ needs. This means that intermediate and secondary schools may choose to make use of the new statements for some students if they are currently working below curriculum level 4, or that primary schools may choose to make use of the existing statements for some students if they are already working above phase 2. Reading, writing, and maths teaching time requirements The teaching and learning of reading, writing,1 and maths2 is a priority for all schools. So that all students are getting sufficient teaching and learning time for reading, writing, and maths, each school board with students in years 0–8 must, through its principal and staff, structure their teaching and learning programmes and/or timetables to provide:

Where reading, writing, and/or maths teaching and learning time is occurring within the context of national curriculum statements other than English or mathematics and statistics, the progression of students’ reading, writing, and/or maths dispositions, knowledge, and skills at the appropriate level must be explicitly and intentionally planned for and attended to. |

Purpose Statement

In the English learning area, students study, use, and engage with language and texts.

Learning in English helps students develop an understanding of the shared codes and conventions of texts and to enjoy and celebrate the beauty and richness of classic and contemporary literature.

The English learning area enables students to access the thoughts and perspectives of others, to walk in different worlds, and to broaden their horizons by experiencing others’ values, ideas, and viewpoints. Exploring texts from different times and places helps students to see how some ideas and language change, while others stay the same. Making meaning of texts provides opportunities for students to strengthen their knowledge and understanding of different perspectives from Aotearoa New Zealand and the wider world.

As text critics, students come to understand how language and texts work and how they change over time, giving them the knowledge and skills to interpret and challenge texts and to create their own meaningful texts. As text creators, students are encouraged to see themselves as members of literary and digital communities, by contributing their own stories and ideas and interpreting the stories and ideas of others.

The English learning area offers meaningful opportunities for students to connect with and use their languages, including te reo Māori and New Zealand Sign Language (NZSL), and their diverse cultural knowledge as resources for learning. The use and development of first and heritage languages enable stronger language and literacy learning and can lead to improved educational outcomes and wellbeing for multilingual learners.

Literacy in English is critical for students to be able to engage successfully with all curriculum learning areas. Being literate and mastering the foundations of oral and written language enable students to be confident and competent learners across the curriculum.

The English learning area plays an important part in developing students’ capacities to think critically and express themselves coherently, fluently, and ethically as active members of society.

Understand-Know-Do overview

English learning area structure

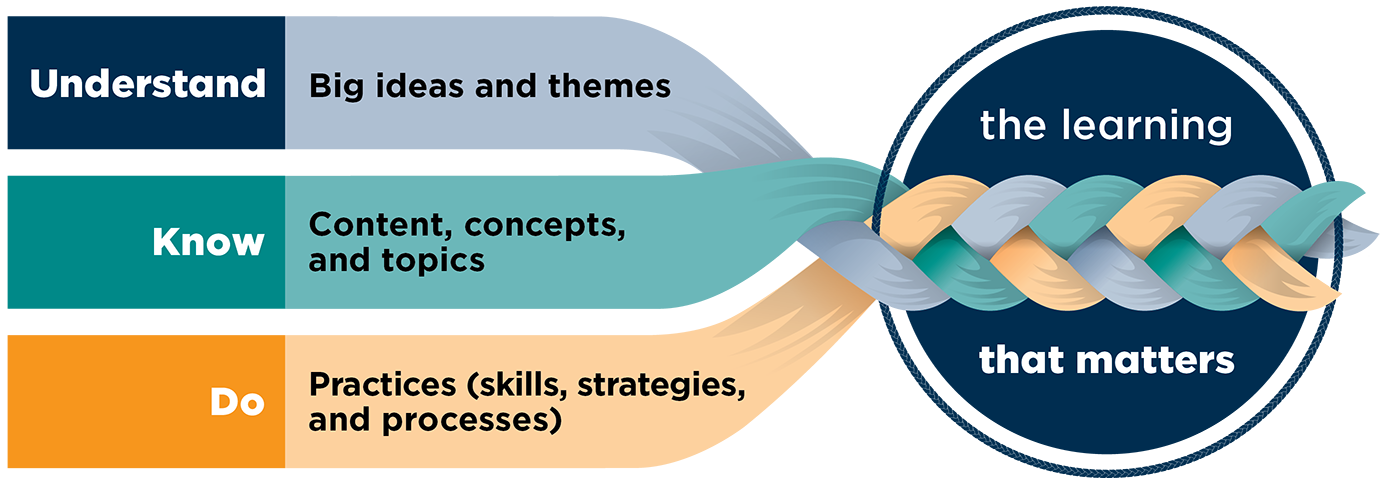

This section describes the English learning area structure and how it changes over the five phases of learning. (See the Content of the learning areas section for the general structure of each learning area in the New Zealand curriculum.)

Each phase has:

- a progress outcome describing what students understand, know, and can do by the end of the phase

- an introduction to the teaching sequence highlighting how to teach during this particular phase

- a year-by-year teaching sequence highlighting what to teach in the phase, along with teaching considerations for particular aspects of content.

Teaching guidance

Key characteristics of how people learn have informed the development of the English learning area. These characteristics are:

- We learn best when we experience a sense of belonging in the learning environment and feel valued and supported.

- A new idea or concept is always interpreted through, and learned in association with, existing knowledge.

- Establishing knowledge in a well-organised way in long-term memory reduces students’ cognitive load when building on that knowledge. It also enables them to apply and transfer the knowledge.

- Our social and emotional wellbeing directly impacts on our ability to learn new knowledge.

- Motivation is critical for wellbeing and engagement in learning.4

All five characteristics are interconnected in a dynamic way. They are always only pieces of the whole, so it is critical to consider them all together. The dynamic and individual nature of learning explains why we see individual learners develop along different paths and at different rates.

The implications of these characteristics for teaching English are described in this section, with more detail in the introduction to each phase and the ‘teaching considerations’ in the year-by-year teaching sequences.

The remainder of this section focuses on three key areas of teacher decision making:

- developing a comprehensive teaching and learning programme

- using assessment to inform teaching

- planning.

Developing a comprehensive teaching and learning programme

A comprehensive English learning area programme needs the following components:

- explicit teaching

- structured literacy approaches

- inclusive teaching and learning

- developing positive identities as communicators, readers, and writers

- working with texts.

Using assessment to inform teaching

Assessment that informs decisions about adapting teaching practice is moment-by-moment and ongoing. Teachers use observation, conversations, and low-stakes testing to continuously monitor students’ progress in relation to their year level in the teaching sequence. They ensure that they notice and recognise the development, consolidation, and use of learning-area knowledge by students within daily lessons, and that they provide timely feedback. They respond by adapting their practice accordingly. For example, they reduce or increase scaffolding and supports, paying particular attention to anxiety caused by cognitive overload. Formative assessment information can also be collected through self and peer assessment, with students reflecting on goals and identifying next steps.

In addition to daily monitoring, teachers use purposefully designed, formative assessment tasks at different points throughout a unit or topic to highlight the concepts and reasoning students use and understand. Teachers ensure such tasks are valid by addressing barriers to learning so that every student is able to demonstrate what they know and can do.

When planning next steps for teaching and learning, teachers consider students’ strengths and responses along with potential opportunities for further consolidation. Next steps could include:

- designing scaffolds to support students to access and enrich their learning

- providing opportunities for students to apply new learning

- planning lessons focused on revisiting, reteaching, or consolidating learning.

Providing timely feedback throughout the learning process and identifying and addressing misconceptions as they arise lead to the efficient and accurate development of learning-area concepts and promote further learning. Teachers can use feedback to prompt students to recall previous learning, make connections, and extend their understanding.

Planning

This section provides guidance on what to pay attention to when planning English teaching and learning programmes. In every classroom, there are many ways in which students engage in learning and show what they know and can do. Using assessment information and designing inclusive experiences, teachers plan an ‘entry point’ to a new concept that every student can access. Students’ interests and the school culture and community shape the planning, adding richness, creativity, and meaning to the programme.

Teaching and learning plans are developed for each year, topic or unit, week, and lesson and make optimal use of instructional time. The following considerations are critical when planning and designing learning:

- Develop plans using the sequence statements for the year, taking students’ prior learning into account. Plan for all students to experience all the statements in the sequence.

- Map out a year’s programme composed of ‘units’ by looking for opportunities to teach statements from the year sequence together. These may be from the same strand or may be across several strands. For example, integrating the teaching of oral language, reading, and writing can be efficient, provided it does not cause cognitive overload for students.

- Order the units so that new learning will build on students’ prior learning and connect over the course of the year. Consider the length of time allocated to specific strands and concepts across the year – some concepts may require more teaching time than others. Ensure the year’s programme includes opportunities to revisit, consolidate, and extend learning around previously taught concepts and processes.

- Within unit or weekly planning, break down the knowledge and skills into a series of manageable learning experiences, so that students have several opportunities to deepen their knowledge. Use assessment information to plan where you will introduce and reinforce learning.

- Identify the key texts you will use that support students to explore, learn, and use these concepts, and provide opportunities to engage in learning that promotes creativity and curiosity.

- Within unit or weekly plans, break down new concepts and procedures into a series of manageable learning experiences, and provide enough opportunities to develop understanding and fluency. Plan for a balance of explicit teaching (to introduce and reinforce learning), and rich tasks (to investigate a concept, support consolidation of previously taught concepts or procedures, and apply learning to new situations). Students should also be given daily opportunities to revisit prior learning. This consolidates and extends their knowledge and practices. Teach both reading and writing for at least an hour each a day (two hours in total), with an understanding that reading and writing are complementary, and will often be taught together.

- Plan for inclusive teaching and learning. Think about multiple ways for students to participate in learning experiences and to show their progress. Plan for equitable access to allow all students to have fair access to learning opportunities. Identify and reduce barriers to learning, and plan for universal supports that are available to all students.

- Use flexible groups within a lesson, based on the learning purpose for the lesson (e.g., working as a whole class for demonstration and discussion, in smaller groups to discuss a text, in pairs to explain thinking). Provide opportunities for both individual and collaborative work, and enable students to determine when they need to work with others and when they need time and space to work independently.

- Teach students to use digital tools accurately, appropriately, and efficiently to enhance meaning making and creation – for example, creating and editing written, visual, and audio text. Plan for students to evaluate the validity, credibility, and accuracy of digital texts. While the use of digital tools is important, students must first learn to read and write print-based text. Handwriting has been shown to reinforce the correct spelling of words and the retention of information, as it involves more cognitive engagement than typing. Therefore, these foundational skills are a key focus in the first two phases of learning.

To support students who have not developed the prior knowledge needed to fully engage with the content of the teaching sequence statements for their year, it is important to find ways to accelerate their progress through such approaches as targeted and explicit small-group teaching.

When students have developed a deep knowledge and consolidated their practices for their year, you can extend their learning by asking them to apply their understanding to unfamiliar situations and more complex texts.

References

1. While the terms reading and writing are used, these expectations are inclusive of alternative methods of communication, including New Zealand Sign Language, augmentative and alternative communication (AAC), and Braille.

2. For simplicity, ‘maths’ is used as an all-encompassing term to refer to the grouping of subject matter, dispositions, skills, competencies, and understandings that encompasses all aspects of numeracy, mathematics, and statistics.

3. “Constrained knowledge and skills consist of a limited number of items and thus can be mastered through systematic teaching within a relatively short time frame. Unconstrained meaning-making knowledge and skills are learned across a lifetime and are broad in scope.” (Scott P. (2005). Reinterpreting the Development of Reading Skills. Reading Research Quarterly, 40/2,184–202.)

4. A description of each characteristic is found here.

5. Oral language encompasses any method of communication a child uses as a first language; this includes New Zealand Sign Language and, for children who are non-verbal, augmentative and alternative communication (AAC).

Abstract nouns |

Nouns that represent ideas, qualities, or states rather than concrete objects. For example, ‘love’, ‘freedom’, ‘happiness’. |

Accountable talk |

A way of speaking and interacting that allows all students to participate in meaningful discussions. It supports students to: share their ideas, respond to the ideas of others respectfully, support their opinions with evidence and engage in sophisticated conversations. |

Adverbial clause |

A group of words that function as an adverb, modifying a verb, adjective, or another adverb. For example, “She sings because she loves music.” |

Alphabetic principle |

The idea or understanding that letters of the alphabet represent specific sounds in speech. |

Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) |

Refers to various methods used to help individuals with speech or language difficulties communicate effectively. AAC includes both augmentative communication, which supplements existing speech, and alternative communication, which replaces speech when it is not possible. |

Automaticity |

The automatic processing of information as, for example, when a reader or writer does not need to pause to work out words as they read or write. The outcome is being a fluent reader, writer and communicator. |

Chameleon prefixes |

Prefixes meaning the same things that can sound or be spelled differently, depending on the first letter of the root word. For example, the prefix ad- (meaning to/toward) changes to ac- when used in the word ‘accept’, or at- in the word ‘attract’. |

Choral reading |

The teacher and the students read the same passage at the same time. |

Clause |

A group of words that includes a subject and a verb. For example, in the sentence, “The baby cries when it is hungry”, “The baby cries” and “when it is hungry” are both clauses. The first one could stand alone as a sentence, so it’s an independent clause. The second one couldn’t stand alone, so it’s a dependent clause. |

Code |

An agreed upon system of signs or symbols used to create meaning within a mode. For example, the code of written language and facial expressions or body language in the gestural mode. |

Complex sentences |

Complex sentences contain one independent clause and one or more dependent clauses. Dependent clauses often begin with subordinating conjunctions like ‘because’, ‘since’, ‘if’, ‘when’, or ‘although’. For example: |

Compound sentences |

Created when two or more independent clauses are joined using a conjunction (such as ‘and’, ‘but’, ‘or’, ‘nor’, ‘for’, ‘so’, or ‘yet’) or a punctuation mark (a semi-colon) to show a connection between two more ideas. Each independent clause in a compound sentence can stand alone as a complete sentence. For example: |

Compound-complex sentence |

These are the most complicated type of sentences. They consist of:

These sentences enable us to articulate more elaborate and detailed thoughts, making them excellent tools for explaining complex ideas or describing extended sequences of events. |

Comprehension monitoring |

Occurs when the reader (or listener) actively monitors and confirms their understanding. They use their prior knowledge of a topic or concept, along with their knowledge of vocabulary, to monitor their understanding of what they are reading or listening to. There are a range of strategies that are used to support meaning making. Students do this from an early age. |

Connective |

Words or phrases that join sentences, clauses, or words together. Connectives can be conjunctions, prepositions, or adverbs. They help to show the relationship between different parts of a sentence or between sentences, helping to make text and spoken language more coherent. There are many connectives to learn about which enhance comprehension and expression of spoken and written language. For example: |

Consonant letters |

Words are written using letters which are either vowels or consonants. English consonant letters are B, C, D, F, G, H, J, K, L, M, N, P, Q, R, S, T, V, W, X, Y (sometimes), Z. |

Consonant phonemes |

A phoneme (speech sound) in which the breath is at least partly obstructed. Consonants are produced by blocking or restricting airflow using the vocal cords and parts of the mouth such as the tongue, lips, or teeth. For example, /s/, /p/, /ch/, and /m/. |

Consonant digraph |

A grapheme written with two or more consonant letters that, together, represent one phoneme. For example, ch- as in ‘chair’ or ph- as in ‘phone’. |

Constrained knowledge and skills |

“Constrained knowledge and skills consist of a limited number of items, such as learning the letters of the alphabet, thus can be mastered through systematic teaching within a relatively short time frame.” - Scott P. (2005). Reinterpreting the Development of Reading Skills. Reading Research Quarterly, 40/2, 184 -2022 |

Convention |

A rule followed by a particular type or mode of language (e.g., for volume when speaking) or a particular type of text (e.g., detective fiction). |

Decodable texts |

Specially designed reading materials used in early literacy instruction. These texts are composed of words that align with the phonics skills students have been taught, allowing them to practice decoding words using their knowledge of letter-sound relationships. |

Decoding strategies |

Strategies used by readers to work out (decode) unfamiliar words. For example, looking for known chunks, using knowledge of grapheme–phoneme relationships. These strategies are essential for developing reading fluency and comprehension. |

Digraph |

Two letters representing one phoneme. This sound is different from the individual sounds of the letters when they are pronounced separately. Digraphs can be composed of either consonants or vowels. For example, -er in ‘her’, -ch in ‘chips’. |

Diphthong |

A sound made by combining two vowels, specifically when it starts as one vowel sound and goes to another, like the ‘oy’ sound in oil. Diphthongs are sometimes called ‘gliding vowels’. |

Echo reading |

First, the teacher reads aloud while students follow along silently. Then students read aloud the same part of the text back to the teacher, echoing the fluency, expression and tone the teacher used. Echo reading can be used for phrases, sentences and paragraphs. |

Emergent bilingual/multilingual |

Students who are developing proficiency in English while continuing to develop their home language(s). |

Explanatory text |

A type of non-fiction writing that explains how or why something happens. It provides a detailed description of a process, event, or concept, often answering questions like “How does this work?” or “Why does this happen?” |

Fluency |

Refers to the ability to express oneself easily and articulately. The ability to speak, read, or write rapidly and accurately, focusing on meaning and phrasing and without having to give attention to individual words or common forms and sequences of language. Fluency is essential in communication as it allows for clear and effective expression, whether in speaking, writing, and reading. |

Fragment |

A fragment is a collection of words that doesn’t form a grammatically complete sentence. Typically, it is missing a subject, a verb, or both, or it is a dependent clause that is not linked to an independent clause. |

Gerunds |

Verb forms ending in -ing that function as nouns. For example, “Swimming is fun.” |

Gist statement |

Summarises the main idea or ‘gist’ of a section of text. |

Global coherence inferences |

Inferences that make the text form a consistent and meaningful whole, so that we can build a mental picture. Common global coherence inferences include ones that suggest the setting of a text or a character’s emotion or goals from key words. |

Grapheme |

The smallest unit of a written language, each usually represents one phoneme. In English, graphemes have one, two, three or four letters. For example, ‘f’, ‘th’, ‘o’, ‘ee’. |

High-frequency words |

Words that appear frequently in written and spoken language and include at least one grapheme-phoneme correspondence that students haven’t been explicitly taught yet or that is so unusual that it is considered irregular. |

Indirect objects |

The recipient of the direct object. For example, “He gave her a gift.” |

Inference |

Inference when reading a text is the process of drawing conclusions or making educated guesses based on the information provided in the text, combined with the reader’s own knowledge and experiences. This process, often described as “reading between the lines” helps readers understand implied meanings, predict outcomes, and grasp deeper insights that are not explicitly stated. |

Interpretation |

The process of assigning meaning or significance to elements within a text based on a student’s understanding, analysis, and personal insights. It involves making connections between various aspects such as characters, events, dialogue, and symbolism to uncover deeper meanings and themes. |

Language features |

Specific techniques used in writing and speech to create or support meaning. These features help convey ideas, evoke emotions, and enhance the overall effectiveness of communication. For example, figurative language and imagery. |

Literacy |

Literacy knowledge and skills underpin and contribute to developing the complex language needed for advanced interpretation and expression of meaning across an increasingly diverse range of oral, visual, written and digital texts. |

Literary texts |

Written works that are valued for their artistic and aesthetic qualities. These texts often explore complex themes, emotions, and human experiences through creative language and storytelling. Literary texts can include various genres, such as: |

Local or lexical inference |

The reader understands the meaning of words and phrases by connecting them to other words and phrases in the text. This is called a lexical inference because it relies on links between lexical items (i.e. words) and is a type of local cohesion inference. |

Meaning making |

Using personal and cultural knowledge, experiences, strategies, and awareness to derive or convey meaning when listening, speaking, reading, writing or viewing; this requires language comprehension, background knowledge, an understanding of the forms and purposes of different text types and an awareness that texts are intended for an audience. |

Metacognition |

Involves being aware of and understanding their own thought processes, which helps them plan, monitor, and evaluate their learning strategies. Linked to the science of learning, this self-awareness enhances their ability to retain information and solve problems. |

Mode |

A system of signs and symbols with agreed upon meanings. Refers to the various forms and methods through which literacy is expressed and communicated. They are essential for developing comprehensive literacy skills, enabling individuals to effectively communicate and understand information in various contexts. Modes of meaning include: |

Morphological knowledge |

An understanding of morphemes, the smallest units of meaning in a language, which can be prefixes, suffixes, or root words. This knowledge is crucial for reading, spelling, and vocabulary development. |

Multimodal text |

Multimodal texts combine two or more modes of communication to convey a message. These modes can include oral language, written language, audio, gestural, spatial and visual modes. Examples of multimodal texts include picture books, websites, performance poetry, films, news reports, infographics, videos, and digital presentations. |

Narrative text |

A type of writing that tells a story or describes a sequence of events. The primary purpose of narrative texts is to entertain or inform the reader by presenting a coherent and engaging story. Organised around events and literary elements such as setting, characters, and a problem and solution. For example, diary, biography, autobiography, personal narrative, fable, myth, legend, fairytale, poem, play. |

Orthographic mapping |

The cognitive process through which a word is permanently stored in memory for instant and effortless recall. Orthographic mapping is crucial for developing fluent reading skills. It enables readers to recognise words automatically without needing to sound them out each time, which frees up cognitive resources for comprehension and higher-order thinking. Key aspects of orthographic mapping include: |

Participles |

Verb forms used as adjectives. Present participles end in -ing, and past participles often end in -ed or -en. For example: |

Partner reading |

One student reads to another, and then they swap roles. Students are taught a simple routine to coach each other through reading errors. |

Phoneme |

The smallest unit of sound in a language that can distinguish one word from another. When combined with other sounds, they form a meaningful unit. For example, the sounds represented by the letters, ‘p’ ‘b’ ‘d’ and ‘t’ are phonemes because they differentiate words like ‘pad,’ ‘bad’ and ‘bat’. |

Phoneme-grapheme correspondence |

The relationships between spoken sound units and the written symbols that represent them. Refers to the relationship between phonemes (the smallest units of sound in a language) and graphemes (the letters or groups of letters that represent those phonemes in written form). This concept (the alphabetic principle) is fundamental in phonics, developing students’ ability to identify and manipulate phonemes and link them to their corresponding graphemes to read and spell words. |

Phonemic awareness |

The ability to hear, differentiate, and attend to the individual sounds within words. A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound in a spoken word. For example, ‘frog’ has four sounds as does the word ‘box’. |

Phonics |

An approach to teaching reading that focuses on the sounds represented by letters in words (see also decoding skills). |

Phonological awareness |

An overall understanding of the sound systems of a language. For example, an awareness that words are made up of combinations of sounds. |

Phrase |

A small group of words within a sentence. It does not make sense on its own. This is because it does not contain a complete verb or a subject. |

Predicate |

The predicate is the part of a sentence (or clause) that states what the subject does or is. For example, in the sentence “Native short-tailed pekapeka hunt insects on the forest floor,” the predicate is “hunt insects on the forest floor”. |

Predicate adjectives |

An adjective that follows a linking verb and describes the subject. For example, “The sky looks blue.” |

Predicate nouns |

A noun that follows a linking verb and renames the subject. For example, “She is a teacher.” |

R-controlled vowel pattern |

Graphemes which represent the phonemes /ar/, /er/, /or/, /eer/, /air/, and /ure/. |

Repeated reading |

Students re-read texts multiple times, focusing on improving accuracy and expression. |

Schwa |

The schwa is the vowel sound in an unstressed syllable. It can be represented by many different letters and often sounds like the short ‘u’ sound ‘uh’ or the short ‘i' sound ‘ih’, like the sound for ‘er’ in letter, or the sound for ‘o’ in police. |

Scope and sequence |

‘Scope’ refers to the concepts or skills that need to be taught. ‘Sequence’ refers to the order in which the concepts and skills are introduced. This ensures that foundational knowledge is built before introducing more complex concepts. This structured approach helps students make connections, facilitating deeper understanding and retention of information. |

Simple sentence |

A simple sentence must:

Simple sentences are the building blocks of more complex sentence structures and are essential for clear and concise communication. Sentences not containing a subject or predicate are ‘incomplete sentences’ or ‘fragments’. |

Self-regulation |

The ability to understand and manage behaviour, emotions, and reactions to various situations. This skill helps children focus on tasks, control impulses, and interact positively with others, all of which are essential for learning and social development. |

Sentence combining |

Sentence combining is an evidence-based instructional technique which is effective for teaching syntax and grammar to children, and improves sentence quality, complexity and variety. |

Split digraph |

A vowel digraph which has been split up by a consonant letter between the two vowel letters. For example: |

Statistical learning |

In the context of reading, statistical learning is the ability to recognise patterns and regularities in written language. It is a form of implicit learning and includes becoming aware of the probability that a particular grapheme will correspond to a particular phoneme. |

Subject |

The person or thing (noun, pronoun, or noun phrase) that a sentence or clause is about. For example, “braided rivers” is the subject in the sentence “braided rivers form many channels”. |

Summarising texts |

Involves condensing the main ideas and key points of a longer text into a shorter version, using your own words. This process helps to provide a clear and concise overview of the original content without including unnecessary details. |

Syllable |

A single, unbroken vowel sound within a spoken word. They typically contain a vowel sound and perhaps one or more accompanying consonants. All words contain at least one syllable. Syllables are sometimes referred to as the 'beats' of a word that form its rhythm, and breaking a word into syllables can help learners with phonetic spelling. |

Syntax |

The rules followed to arrange words and phrases to create logical and grammatically correct clauses, and sentences. It involves the rules that govern the structure of sentences, including word order, sentence structure, and the relationship between words. |

Systematic synthetic phonics |

A method of teaching reading that emphasises the relationship between letters (graphemes) and sounds (phonemes) in a structured and sequential manner. The term ‘synthetic’ comes from the synthesising or blending of sounds to make a word and enable children to read. |

Taonga tuku iho |

Something handed down, a cultural property or heritage. |

Text |

Texts are constructed from one or more of the modes of meaning (oral language, written language, audio, gestural, spatial and visual modes). They are a language event that we require language skills to understand. Creators construct texts to convey meaning to an audience. For example, a speech, poem, poster, video clip, advertisement. |

Text type |

A particular kind of text with features and conventions linked to its purpose. For example, oral texts are spoken forms of communication, like speeches and conversations, while written texts are conveyed through writing, such as books and articles. Digital texts, created and accessed using technology, often include interactive elements like audio and video. |

Text creator |

An individual or group who creates texts in any mode and using any technology. |

Think-alouds |

A teaching strategy where teachers verbalise their thought processes. |

Transcription |

Describes the act of converting spoken language into written form on the page or screen. |

Trigraph |

A cluster of three letters that collectively produce a specific single sound. It can be composed entirely of consonants or vowels, or it can be a mix of both. For example, sigh, catch |

Unconstrained knowledge and skills |

“Unconstrained meaning-making knowledge and skills are learned across a lifetime and are broad in scope.” - Scott P. (2005). Reinterpreting the Development of Reading Skills. Reading Research Quarterly, 40/2, 184-202 |

Unstressed syllable |

The part of the word that doesn't receive emphasis or stress. |

Vowel |

Words are built from letters which are either vowels or consonants. Vowels are A, E, I, O, U and sometimes Y. All syllables include vowels. |

Vowel team |

A spelling pattern where two or more letters are used to represent a single vowel sound. This includes vowel digraphs but also combinations of two or more letters (e.g., -igh for /ī/). |

Worked examples |

A teaching strategy that provides students with step-by-step demonstrations or examples of how to solve a problem or complete a task. |