About this resource

This page provides the progress outcome and teaching sequence for Phase 2 (Year 4-6) of the English learning area of the New Zealand Curriculum, the official document that sets the direction for teaching, learning, and assessment in all English medium state and state-integrated schools in New Zealand. In English, students study, use, and enjoy language and literature communicated orally, visually, or in writing. It comes into effect on 1 January 2025. Other parts of the learning area are provided on companion pages.

We have also provided the English Year 0-6 curriculum in PDF format. There are different versions available for printing (spreads), viewing online (single page), and to view by phase. You can access these using the icons below. Use your mouse and hover over each icon to see the document description.

File Downloads

No files available for download.

Te Mātaiaho | The New Zealand Curriculum English: Phase 2 – Years 4-6 |

Expanding horizons of knowledge, and collaborating |

Progress outcome by the end of year 6

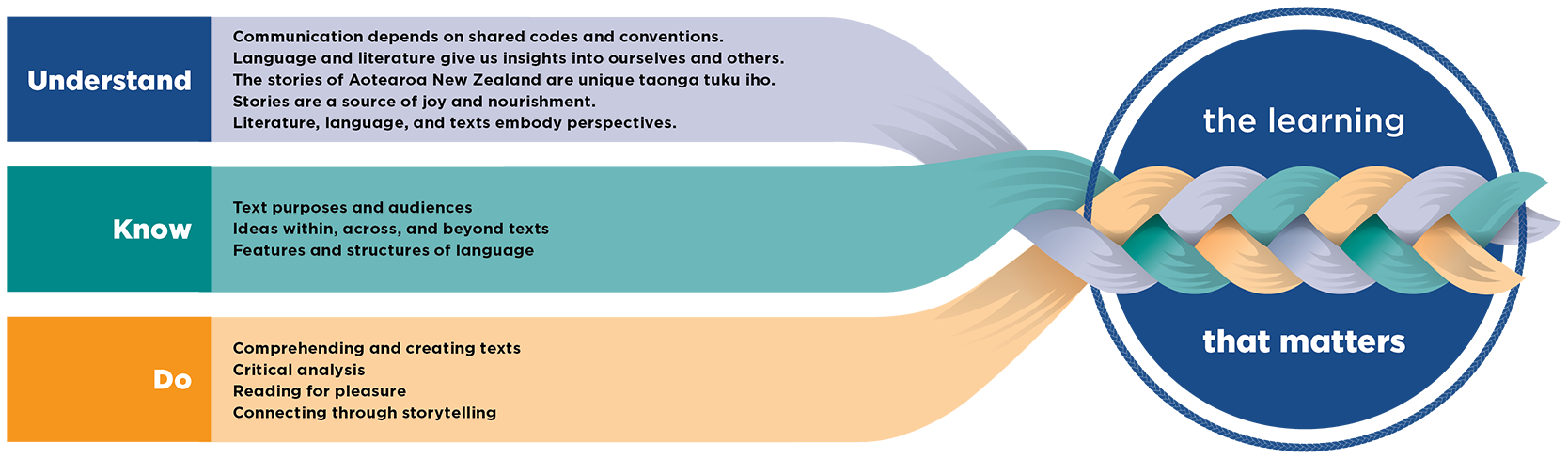

The critical focus of phase 2 is for all students to expand their horizons of knowledge and their collaboration, while continuing to nurture a positive relationship with oral language, reading, and writing. Throughout this phase there is a greater emphasis on using literacy in all learning areas and increasing students’ overall and subject-specific knowledge.

Through an emphasis on communicating for learning, students enhance their ability to acquire knowledge through communication, in response to frequent opportunities to articulate their thoughts and ideas.

In reading, students consolidate their automatic word-recognition skills and further develop a love of reading. In writing, they explore diverse topics and genres with increasing technical accuracy, fostering creativity and enhancing their communication skills.

Students have opportunities to consolidate their learning through written text, as well as through visual and oral modes, and begin to use a range of digital technologies. As they use their literacy capabilities in increasingly specialised ways, students gain a more nuanced understanding of language codes and conventions, and how their use changes depending on context and purpose. Students deepen their understanding of the role of story in people’s lives and the ability of stories to shape lives. They understand that stories from New Zealand and the wider world are a source of insight into places and people. They also understand the influence of texts on themselves and on those who are represented in and by texts.

The phase 2 progress outcome describes the understanding, knowledge, and practices that students have multiple opportunities to develop over the phase.

The phase 2 progress outcome is found below in the following table.

Teaching sequence – Phase 2 (Years 4-6)

Expanding horizons of knowledge, and collaborating |

This section describes how the components of a comprehensive English teaching and learning programme are used during the second phase of learning at school.

In phase 2, such a programme offers students teaching that inspires the enjoyment of language and texts and provides systematic, explicit teaching of oral language, reading, and writing.

Students will continue to build their skills and knowledge with written texts while also encountering and engaging with texts and text features in a range of other modes (e.g., spoken, visual, and multimodal).

Continuously monitor students’ learning and respond quickly to address any issues and misconceptions. Ensure teaching builds on what students already understand, know, and can do.

Oral language

- | During year 4 | During year 5 | During year 6 | Teaching considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Communicating ideas and information |

|

|

| Regular, deliberate practice builds confidence and fluency in the use of increasingly complex narrative language. Examples of techniques for teaching recounting, retelling, and generating narratives include:

|

Communicating ideas and information |

|

|

| Examples of techniques for teaching presenting to others include:

|

Communicating ideas and information |

|

|

| Teach taking on roles using techniques such as:

|

Interpersonal communication |

|

|

| Be mindful of cultural differences and unique neurodivergent preferences when teaching about non-verbal communication, as these can influence interpretations and degree of familiarity and comfort. Teach non-verbal communication using techniques such as:

|

Interpersonal communication |

|

|

| Teach listening and responding to others through techniques such as:

|

Interpersonal communication |

|

|

| Be mindful of cultural differences and unique neurodivergent preferences when teaching about tone, volume, and pace, as these can influence interpretations and degree of familiarity and comfort. Teach tone, volume, and pace through techniques such as:

|

Vocabulary and grammar |

|

|

| Teaching vocabulary is an essential component of building knowledge; both knowledge of how language works and content knowledge across the curriculum. Students learn and retain new vocabulary most effectively by learning words within thematic units, sustained over time. Introduce abstract and discipline-specific vocabulary by explicitly teaching pronunciation, meaning, spelling, morphology, etymology, related words, and usage in sentences. Connect new vocabulary to students’ existing knowledge to foster deeper understanding. Provide opportunities for deliberate practice and frequent review to solidify students’ grasp of new vocabulary by, for example, using role play to apply new vocabulary in realistic scenarios, and incorporating new vocabulary into their storytelling and personal narratives. Consider using videos, podcasts, and audio recordings that feature new vocabulary, providing diverse opportunities for students to hear and understand words in context. |

Vocabulary and grammar |

|

|

| Teaching sentence structure and morphological awareness explicitly through oral language in all curriculum areas helps students express their thoughts and ideas clearly and precisely, supporting learning across the curriculum. The teaching of specific sentence structures can occur both explicitly and incidentally. Introduce new sentence structures within topics familiar to students. Subsequently, embed speaking and listening practice within learning, throughout all curriculum areas rather than in isolated grammar lessons. Teach these skills through techniques such as:

|

Communication for learning |

|

|

| Teaching metacognition and self-regulation in this phase involves helping students become aware of their own thinking processes and actions, and how to manage these to improve their learning through discussion and self-talk. Build these skills through techniques such as:

|

Communication for learning |

|

|

| Work towards students independently selecting and applying strategies that they have identified as being effective for their own learning. Build these skills through techniques such as:

|

Reading

Working with year-level texts

The texts that students read become increasingly complex over time, supporting them to succeed both in English and in all other learning areas at each year level. For this to occur, when the purpose for reading is other than learning decoding or reading for pleasure, students need opportunities to engage with texts at or above the complexity described for each year level. Although fluent readers may still work with simple texts, particularly to reduce cognitive load when new skills and concepts are being introduced, they will be working predominantly with texts that are at least at their year level. This does not mean you should prevent able readers from reading more complex texts; most texts will be at their year level or above.

Noticing, recognising, and responding to students’ strengths and needs

Except when they are specifically learning to decode text or reading for pleasure, students who are still consolidating their decoding skills need to access year-level texts to develop skills and knowledge (including vocabulary, comprehension, and content knowledge) alongside their peers. Help students do this by adapting the supports and scaffolds for students, rather than by simplifying or modifying texts. An effective way to accelerate students’ learning is to explicitly teach the features of year-level texts that carry meaning. This will enable them to make sense of texts that are above their traditional ‘instructional level’. When this is not possible, remove barriers and provide alternative ways to access year-level texts, for example, by using audio versions or print-to-speech software. Students who need to accelerate their decoding skills will continue to require frequent, intensive, and explicit teaching and practice in flexible small groups, targeting their decoding needs.

Students who reach fluency and comprehension mastery at an accelerated rate of progress need opportunities for enrichment and extension, and ample opportunity to read increasingly challenging texts.

- | During year 4 | During year 5 | During year 6 | Teaching considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Word recognition and reading enrichment |

| Explicitly teach students to use their learned knowledge of grapheme-phoneme correspondence, morphemes, syllables, and words to decode and orthographically map multi-syllable and more complex new words. Some phase 2 students will still be working through a decoding scope and sequence, so it is important that they receive the explicit teaching they need to become proficient readers and writers. Use diagnostic formative assessment to identify their needs and strengths and to design accelerative and intensive targeted teaching, using age-appropriate materials. While these students continue to build their foundational skills in reading and writing, scaffold their access to year-level texts so that they can continue to build vocabulary, content knowledge, and comprehension skills at their year level. Refer to the Ministry’s online guidance on targeted teaching. The guides on the Ministry’s Inclusive Education website include details of effective teaching strategies for responding to a range of learning needs. For emergent bilingual and multilingual students, use the Ministry’s English Language Learning Progressions (ELLP) and ELLP Pathway and Pacific dual language books to support your teaching. For Deaf or hard-of-hearing students, make use of the Ministry’s New Zealand Sign Language resources and e-books to support your teaching. | ||

Word recognition and reading enrichment |

|

|

| Fluent reading – with accuracy, appropriate rate, automaticity, and expression – is necessary for reading comprehension. Use an Oral Reading Fluency (ORF) assessment to identify students needing more targeted teaching support and to monitor progress and acceleration regularly over time. If students are not reading with sufficient fluency at phase 2, this may indicate difficulty with foundational decoding skills. Fluency teaching and interventions should target reading accuracy, phrasing, and expression. ‘Fast’ reading is not the aim. Support students to develop their fluency through evidence-based strategies such as:

|

Word recognition and reading enrichment |

| Provide opportunities for students to select texts based on their preferences and interests. These may include texts that are above or below their year level. Establish a reading community where students listen, read, and make text recommendations. Positively influence students’ relationships with reading by providing positive learning experiences. Set relevant and meaningful learning objectives and offer high-interest texts. Give students choice, opportunities to collaborate, and challenging tasks, and recognise success. Model a positive reader identity by sharing your own relationship with reading in a positive way. For example, regularly share your reading with students as a way of modelling curiosity, enjoyment, and how to overcome reading challenges. Help students recognise that stories can be a source of joy and nourishment. | ||

Comprehension |

|

|

| Vocabulary knowledge is vital for reading comprehension. Develop students’ vocabulary by immersing them in sophisticated language across learning areas throughout the school day. Provide multiple opportunities for students to hear new words, in conversations and through engaging with increasingly complex texts, and to practise pronouncing them correctly. Provide opportunities to make connections with the vocabulary and linguistic knowledge that students bring with them. For some students, new vocabulary learning will centre on less-common words and words that express abstract concepts. In addition, ELLs and students with language-related learning challenges will benefit from explicit teaching and incidental support for more common, everyday vocabulary. Teach students about the meanings of word parts and their origins to help them work out the meaning of unknown words. This may include teaching students to break down words into their base words, prefixes, and suffixes when helpful and relevant (e.g., understanding that ‘unhappy’ means ‘not happy’ because of the prefix ‘un-’). Teach students to use context clues to determine the meaning of unknown words. Model how to use context clues by thinking aloud while reading (e.g., “I don’t know this word, but the sentence says the creature lives in trees, so ‘arboreal’ must mean something related to trees.”). Context clues should only be used to work out the meaning of words. They are not used to work out what the word is, although they may sometimes alert the reader that they have made a decoding error when meaning is lost. |

Comprehension |

|

|

| Whole-text comprehension is largely dependent on both general knowledge and vocabulary knowledge, so teach these throughout the school day. Provide opportunities for students to read often and widely so they engage with a range of texts for enjoyment and to build knowledge. Provide examples of a range of genres and forms. For example, explore the differences between different poetic forms, including language choices and structure. Students need to have exposure to texts specific to Aotearoa New Zealand and global texts to expand their horizons of knowledge. By comparing and contrasting these texts, paying particular attention to texts valuing te ao Māori and Māori perspectives, they identify what makes Aotearoa New Zealand unique. To further their understanding of what it means to live in the Pacific, they need to engage with texts by Pacific authors and others who have made New Zealand their home. Explicitly teach the different purposes for writing and the features and structures of texts through, for example, the use of exemplar texts. Ensure that the complexity of the text is appropriate. |

Comprehension |

|

|

| |

Comprehension |

|

|

| Talk through your own thought processes to model what students should do when they find problems in texts (e.g., unknown words, conflicts with prior knowledge, and inconsistencies). Demonstrate what they can do to solve those problems. For example, ask questions during and after reading or listening to a text such as, “Does that make sense?”, “Why did ...?”, “How does that connect with ...?”, or “How does this information fit with what I already know about this topic?”. Support students to visualise a story as a series of mental images. This helps some students remember details more accurately, supports the integration of information across the text, and helps them to detect inconsistencies. |

Comprehension |

|

|

| Summarising and drawing conclusions are powerful skills to teach because they improve students’ memory of what they have read and can also be used as a comprehension check. Explicitly teach summarising and drawing conclusions with a range of different texts, across the curriculum. Teach these skills through techniques such as:

|

Comprehension |

|

|

| During read-aloud sessions, pause to ask students what is happening and why. Encourage them to use evidence from the text to support their answers. Model the process of making inferences by thinking aloud. Show students how you use your knowledge and clues from the text to draw conclusions. Encourage students to ask questions about the text. Questions such as “Why did the character do that?” or “What might happen next?” can lead to deeper understanding and help students practise making inferences. You may want to organise group discussions or debates on a text. Encourage students to present their inferences and defend them with textual evidence. This promotes critical thinking and deeper engagement with the material. |

Critical analysis |

|

|

| Provide students with a wide range of texts, including information texts, stories, poems, and plays that provide them with the opportunity to form opinions, make connections and inferences, and identify perspectives. Develop critical analysis skills by helping students uncover the perspectives and positions that underpin texts, including their own, and the impact of these. Teach students to understand the difference between fact and opinion, and information and disinformation. Equip students with the skills to identify and affirm, or resist, the positions and perspectives put forward in texts, in both print and digital formats. Explicitly teach students:

Ask questions to prompt students to share their perspectives:

|

Critical analysis |

|

|

| The different kinds of knowledge that students bring to text, including topic, disciplinary, cultural, and general knowledge, all contribute to their understanding of texts. Explicitly teach students not only to use their existing knowledge, but also to refine it by seeking new information. Classroom environments need to be safe places where students feel comfortable sharing their knowledge, so that different perspectives can be heard and understood. Teachers need to deliberately build knowledge through complex, rich texts and experiences and discussions that build depth and breadth of this knowledge. Using questioning before, during, and after reading can provide opportunities to check your understanding of the knowledge that students have, and are developing, as they read. This approach can also be applied when students are creating their own texts. |

|

|

| ||

Writing

- | During year 4 | During year 5 | During year 6 | Teaching considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Transcription skills |

|

|

| Using a consistent, school-wide approach, teach handwriting explicitly, every day. In phase 2, it is expected that most students will be forming letters correctly. Focus now on automaticity and building increased handwriting stamina. Support students with their handwriting during writing time, and encourage them to practise their best handwriting every time they write. If handwriting difficulties persist after an extended period of appropriate instruction, consider using assistive technologies to support composition. |

|

|

| ||

Transcription skills | - | - |

| Ensure students are explicitly shown how to use a keyboard, including the use of the shift key to access capital letters and additional punctuation. |

Transcription skills |

|

|

| Symbols used in the sequence: the content within <> is the grapheme and within // is the phoneme. Teach spelling every day. While most phase 2 students will be fluent decoders, all will still require explicit instruction in spelling. Spelling is a more complex process, which requires deep knowledge of the ways in which the same phonemes can be represented by different graphemes. Students need to learn which are the correct graphemes to use for any particular word. Provide multiple, spaced opportunities for deliberate practice and review. Explicitly teach students:

Support students to apply their spelling knowledge and skills during writing composition, providing prompt feedback and positive error corrections. |

spell words with:

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

|

| - | ||

|

|

| ||

|

| - | ||

|

|

| ||

| - | - | ||

Composition |

|

|

| When analysing model texts for writing, and during shared reading, explicitly teach students:

Provide opportunities for students to share their writing with different audiences and in different forms. |

Composition |

|

|

| Explicitly teach sentence structures and punctuation using sentence-combining, explanations, and modelling. Students who can write well-constructed sentences with ease free up their working memory to focus on content. Teach sentence structures and punctuation through activities such as:

Some students will benefit from scaffolding and supports such as colour coding, graphics, and manipulatives to identify the different parts of a sentence. |

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

|

| - | ||

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

Composition |

|

|

| Writing should always have a purpose – for example:

Students’ awareness of text structures and purposes begins during reading. Explicitly teach students how to recognise text structures as they read. This supports their reading comprehension as well as their writing composition. Use exemplar texts to explicitly teach students to recognise the structures and key features (titles, headings, diagrams, illustrations, order of events, and language used) of different text types during reading and writing. As students move through this phase and write more, use specific text-type planning templates to support students to include essential elements of the text type (e.g., a persuasive piece would use a different planning template from a fairy tale). For each text type, students will need explicit teaching for:

|

Composition |

|

|

| |

Composition |

|

|

| |

Composition | - |

|

| Scaffold the creation of digital texts by explicitly teaching and modelling how to access and use word processing programs, including their editing tools. Support students to develop critical analysis skills and to use these to make decisions about selecting content for their digital texts (e.g., when selecting from the internet). |

Writing craft |

|

|

| When teaching word choice:

Poetry is a rich source of vivid and imaginative word choice. Reading and writing poetry gives students the chance to encounter a rich store of words and use them in innovative and creative ways. During this phase, word choice should become a more deliberate act, and this needs to be modelled by the teacher. |

Writing craft |

|

|

| Introduce the language feature or literary device by giving its name, a definition suitable for the year level, examples of its use, and the effect it has. Teach language features and devices through such activities as:

|

Writing processes |

|

|

| Ensure students are writing daily and are encouraged to write across the curriculum. This may be done independently or collaboratively. When collaborating, students need to respect the contributions everyone brings. The writing process is recursive. Effective writers continually revisit and repeat the stages in the process as they write. Build students’ knowledge about the topics they are going to plan and write about through reading to, reading with, research, experiences, and discussion. Explicitly teach the components of the writing process using think-alouds, modelling, and exemplar texts. Use planning templates that promote a clear paragraph and multi-paragraph structure (introductions, body, and conclusions) to support students to write using these structures. Explicitly teach students how to organise content by grouping it into relevant paragraphs during planning. Teach writing processes through focusing on:

Giving and receiving feedback will be part of both revising for message and purpose and editing for conventions such as spelling and punctuation. It will also help identify areas for goal setting. |

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

Writing processes |

|

|

| |

|

|

| ||

| ||||

Writing processes |

|

|

| |

|

|

| ||

- |

|

| ||

Writing processes |

|

|

| |

|

|

| ||

|

|

| ||

Abstract nouns |

Nouns that represent ideas, qualities, or states rather than concrete objects. For example, ‘love’, ‘freedom’, ‘happiness’. |

Accountable talk |

A way of speaking and interacting that allows all students to participate in meaningful discussions. It supports students to: share their ideas, respond to the ideas of others respectfully, support their opinions with evidence and engage in sophisticated conversations. |

Adverbial clause |

A group of words that function as an adverb, modifying a verb, adjective, or another adverb. For example, “She sings because she loves music.” |

Alphabetic principle |

The idea or understanding that letters of the alphabet represent specific sounds in speech. |

Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) |

Refers to various methods used to help individuals with speech or language difficulties communicate effectively. AAC includes both augmentative communication, which supplements existing speech, and alternative communication, which replaces speech when it is not possible. |

Automaticity |

The automatic processing of information as, for example, when a reader or writer does not need to pause to work out words as they read or write. The outcome is being a fluent reader, writer and communicator. |

Chameleon prefixes |

Prefixes meaning the same things that can sound or be spelled differently, depending on the first letter of the root word. For example, the prefix ad- (meaning to/toward) changes to ac- when used in the word ‘accept’, or at- in the word ‘attract’. |

Choral reading |

The teacher and the students read the same passage at the same time. |

Clause |

A group of words that includes a subject and a verb. For example, in the sentence, “The baby cries when it is hungry”, “The baby cries” and “when it is hungry” are both clauses. The first one could stand alone as a sentence, so it’s an independent clause. The second one couldn’t stand alone, so it’s a dependent clause. |

Code |

An agreed upon system of signs or symbols used to create meaning within a mode. For example, the code of written language and facial expressions or body language in the gestural mode. |

Complex sentences |

Complex sentences contain one independent clause and one or more dependent clauses. Dependent clauses often begin with subordinating conjunctions like ‘because’, ‘since’, ‘if’, ‘when’, or ‘although’. For example: |

Compound sentences |

Created when two or more independent clauses are joined using a conjunction (such as ‘and’, ‘but’, ‘or’, ‘nor’, ‘for’, ‘so’, or ‘yet’) or a punctuation mark (a semi-colon) to show a connection between two more ideas. Each independent clause in a compound sentence can stand alone as a complete sentence. For example: |

Compound-complex sentence |

These are the most complicated type of sentences. They consist of:

These sentences enable us to articulate more elaborate and detailed thoughts, making them excellent tools for explaining complex ideas or describing extended sequences of events. |

Comprehension monitoring |

Occurs when the reader (or listener) actively monitors and confirms their understanding. They use their prior knowledge of a topic or concept, along with their knowledge of vocabulary, to monitor their understanding of what they are reading or listening to. There are a range of strategies that are used to support meaning making. Students do this from an early age. |

Connective |

Words or phrases that join sentences, clauses, or words together. Connectives can be conjunctions, prepositions, or adverbs. They help to show the relationship between different parts of a sentence or between sentences, helping to make text and spoken language more coherent. There are many connectives to learn about which enhance comprehension and expression of spoken and written language. For example: |

Consonant letters |

Words are written using letters which are either vowels or consonants. English consonant letters are B, C, D, F, G, H, J, K, L, M, N, P, Q, R, S, T, V, W, X, Y (sometimes), Z. |

Consonant phonemes |

A phoneme (speech sound) in which the breath is at least partly obstructed. Consonants are produced by blocking or restricting airflow using the vocal cords and parts of the mouth such as the tongue, lips, or teeth. For example, /s/, /p/, /ch/, and /m/. |

Consonant digraph |

A grapheme written with two or more consonant letters that, together, represent one phoneme. For example, ch- as in ‘chair’ or ph- as in ‘phone’. |

Constrained knowledge and skills |

“Constrained knowledge and skills consist of a limited number of items, such as learning the letters of the alphabet, thus can be mastered through systematic teaching within a relatively short time frame.” - Scott P. (2005). Reinterpreting the Development of Reading Skills. Reading Research Quarterly, 40/2, 184 -2022 |

Convention |

A rule followed by a particular type or mode of language (e.g., for volume when speaking) or a particular type of text (e.g., detective fiction). |

Decodable texts |

Specially designed reading materials used in early literacy instruction. These texts are composed of words that align with the phonics skills students have been taught, allowing them to practice decoding words using their knowledge of letter-sound relationships. |

Decoding strategies |

Strategies used by readers to work out (decode) unfamiliar words. For example, looking for known chunks, using knowledge of grapheme–phoneme relationships. These strategies are essential for developing reading fluency and comprehension. |

Digraph |

Two letters representing one phoneme. This sound is different from the individual sounds of the letters when they are pronounced separately. Digraphs can be composed of either consonants or vowels. For example, -er in ‘her’, -ch in ‘chips’. |

Diphthong |

A sound made by combining two vowels, specifically when it starts as one vowel sound and goes to another, like the ‘oy’ sound in oil. Diphthongs are sometimes called ‘gliding vowels’. |

Echo reading |

First, the teacher reads aloud while students follow along silently. Then students read aloud the same part of the text back to the teacher, echoing the fluency, expression and tone the teacher used. Echo reading can be used for phrases, sentences and paragraphs. |

Emergent bilingual/multilingual |

Students who are developing proficiency in English while continuing to develop their home language(s). |

Explanatory text |

A type of non-fiction writing that explains how or why something happens. It provides a detailed description of a process, event, or concept, often answering questions like “How does this work?” or “Why does this happen?” |

Fluency |

Refers to the ability to express oneself easily and articulately. The ability to speak, read, or write rapidly and accurately, focusing on meaning and phrasing and without having to give attention to individual words or common forms and sequences of language. Fluency is essential in communication as it allows for clear and effective expression, whether in speaking, writing, and reading. |

Fragment |

A fragment is a collection of words that doesn’t form a grammatically complete sentence. Typically, it is missing a subject, a verb, or both, or it is a dependent clause that is not linked to an independent clause. |

Gerunds |

Verb forms ending in -ing that function as nouns. For example, “Swimming is fun.” |

Gist statement |

Summarises the main idea or ‘gist’ of a section of text. |

Global coherence inferences |

Inferences that make the text form a consistent and meaningful whole, so that we can build a mental picture. Common global coherence inferences include ones that suggest the setting of a text or a character’s emotion or goals from key words. |

Grapheme |

The smallest unit of a written language, each usually represents one phoneme. In English, graphemes have one, two, three or four letters. For example, ‘f’, ‘th’, ‘o’, ‘ee’. |

High-frequency words |

Words that appear frequently in written and spoken language and include at least one grapheme-phoneme correspondence that students haven’t been explicitly taught yet or that is so unusual that it is considered irregular. |

Indirect objects |

The recipient of the direct object. For example, “He gave her a gift.” |

Inference |

Inference when reading a text is the process of drawing conclusions or making educated guesses based on the information provided in the text, combined with the reader’s own knowledge and experiences. This process, often described as “reading between the lines” helps readers understand implied meanings, predict outcomes, and grasp deeper insights that are not explicitly stated. |

Interpretation |

The process of assigning meaning or significance to elements within a text based on a student’s understanding, analysis, and personal insights. It involves making connections between various aspects such as characters, events, dialogue, and symbolism to uncover deeper meanings and themes. |

Language features |

Specific techniques used in writing and speech to create or support meaning. These features help convey ideas, evoke emotions, and enhance the overall effectiveness of communication. For example, figurative language and imagery. |

Literacy |

Literacy knowledge and skills underpin and contribute to developing the complex language needed for advanced interpretation and expression of meaning across an increasingly diverse range of oral, visual, written and digital texts. |

Literary texts |

Written works that are valued for their artistic and aesthetic qualities. These texts often explore complex themes, emotions, and human experiences through creative language and storytelling. Literary texts can include various genres, such as: |

Local or lexical inference |

The reader understands the meaning of words and phrases by connecting them to other words and phrases in the text. This is called a lexical inference because it relies on links between lexical items (i.e. words) and is a type of local cohesion inference. |

Meaning making |

Using personal and cultural knowledge, experiences, strategies, and awareness to derive or convey meaning when listening, speaking, reading, writing or viewing; this requires language comprehension, background knowledge, an understanding of the forms and purposes of different text types and an awareness that texts are intended for an audience. |

Metacognition |

Involves being aware of and understanding their own thought processes, which helps them plan, monitor, and evaluate their learning strategies. Linked to the science of learning, this self-awareness enhances their ability to retain information and solve problems. |

Mode |

A system of signs and symbols with agreed upon meanings. Refers to the various forms and methods through which literacy is expressed and communicated. They are essential for developing comprehensive literacy skills, enabling individuals to effectively communicate and understand information in various contexts. Modes of meaning include: |

Morphological knowledge |

An understanding of morphemes, the smallest units of meaning in a language, which can be prefixes, suffixes, or root words. This knowledge is crucial for reading, spelling, and vocabulary development. |

Multimodal text |

Multimodal texts combine two or more modes of communication to convey a message. These modes can include oral language, written language, audio, gestural, spatial and visual modes. Examples of multimodal texts include picture books, websites, performance poetry, films, news reports, infographics, videos, and digital presentations. |

Narrative text |

A type of writing that tells a story or describes a sequence of events. The primary purpose of narrative texts is to entertain or inform the reader by presenting a coherent and engaging story. Organised around events and literary elements such as setting, characters, and a problem and solution. For example, diary, biography, autobiography, personal narrative, fable, myth, legend, fairytale, poem, play. |

Orthographic mapping |

The cognitive process through which a word is permanently stored in memory for instant and effortless recall. Orthographic mapping is crucial for developing fluent reading skills. It enables readers to recognise words automatically without needing to sound them out each time, which frees up cognitive resources for comprehension and higher-order thinking. Key aspects of orthographic mapping include: |

Participles |

Verb forms used as adjectives. Present participles end in -ing, and past participles often end in -ed or -en. For example: |

Partner reading |

One student reads to another, and then they swap roles. Students are taught a simple routine to coach each other through reading errors. |

Phoneme |

The smallest unit of sound in a language that can distinguish one word from another. When combined with other sounds, they form a meaningful unit. For example, the sounds represented by the letters, ‘p’ ‘b’ ‘d’ and ‘t’ are phonemes because they differentiate words like ‘pad,’ ‘bad’ and ‘bat’. |

Phoneme-grapheme correspondence |

The relationships between spoken sound units and the written symbols that represent them. Refers to the relationship between phonemes (the smallest units of sound in a language) and graphemes (the letters or groups of letters that represent those phonemes in written form). This concept (the alphabetic principle) is fundamental in phonics, developing students’ ability to identify and manipulate phonemes and link them to their corresponding graphemes to read and spell words. |

Phonemic awareness |

The ability to hear, differentiate, and attend to the individual sounds within words. A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound in a spoken word. For example, ‘frog’ has four sounds as does the word ‘box’. |

Phonics |

An approach to teaching reading that focuses on the sounds represented by letters in words (see also decoding skills). |

Phonological awareness |

An overall understanding of the sound systems of a language. For example, an awareness that words are made up of combinations of sounds. |

Phrase |

A small group of words within a sentence. It does not make sense on its own. This is because it does not contain a complete verb or a subject. |

Predicate |

The predicate is the part of a sentence (or clause) that states what the subject does or is. For example, in the sentence “Native short-tailed pekapeka hunt insects on the forest floor,” the predicate is “hunt insects on the forest floor”. |

Predicate adjectives |

An adjective that follows a linking verb and describes the subject. For example, “The sky looks blue.” |

Predicate nouns |

A noun that follows a linking verb and renames the subject. For example, “She is a teacher.” |

R-controlled vowel pattern |

Graphemes which represent the phonemes /ar/, /er/, /or/, /eer/, /air/, and /ure/. |

Repeated reading |

Students re-read texts multiple times, focusing on improving accuracy and expression. |

Schwa |

The schwa is the vowel sound in an unstressed syllable. It can be represented by many different letters and often sounds like the short ‘u’ sound ‘uh’ or the short ‘i' sound ‘ih’, like the sound for ‘er’ in letter, or the sound for ‘o’ in police. |

Scope and sequence |

‘Scope’ refers to the concepts or skills that need to be taught. ‘Sequence’ refers to the order in which the concepts and skills are introduced. This ensures that foundational knowledge is built before introducing more complex concepts. This structured approach helps students make connections, facilitating deeper understanding and retention of information. |

Simple sentence |

A simple sentence must:

Simple sentences are the building blocks of more complex sentence structures and are essential for clear and concise communication. Sentences not containing a subject or predicate are ‘incomplete sentences’ or ‘fragments’. |

Self-regulation |

The ability to understand and manage behaviour, emotions, and reactions to various situations. This skill helps children focus on tasks, control impulses, and interact positively with others, all of which are essential for learning and social development. |

Sentence combining |

Sentence combining is an evidence-based instructional technique which is effective for teaching syntax and grammar to children, and improves sentence quality, complexity and variety. |

Split digraph |

A vowel digraph which has been split up by a consonant letter between the two vowel letters. For example: |

Statistical learning |

In the context of reading, statistical learning is the ability to recognise patterns and regularities in written language. It is a form of implicit learning and includes becoming aware of the probability that a particular grapheme will correspond to a particular phoneme. |

Subject |

The person or thing (noun, pronoun, or noun phrase) that a sentence or clause is about. For example, “braided rivers” is the subject in the sentence “braided rivers form many channels”. |

Summarising texts |

Involves condensing the main ideas and key points of a longer text into a shorter version, using your own words. This process helps to provide a clear and concise overview of the original content without including unnecessary details. |

Syllable |

A single, unbroken vowel sound within a spoken word. They typically contain a vowel sound and perhaps one or more accompanying consonants. All words contain at least one syllable. Syllables are sometimes referred to as the 'beats' of a word that form its rhythm, and breaking a word into syllables can help learners with phonetic spelling. |

Syntax |

The rules followed to arrange words and phrases to create logical and grammatically correct clauses, and sentences. It involves the rules that govern the structure of sentences, including word order, sentence structure, and the relationship between words. |

Systematic synthetic phonics |

A method of teaching reading that emphasises the relationship between letters (graphemes) and sounds (phonemes) in a structured and sequential manner. The term ‘synthetic’ comes from the synthesising or blending of sounds to make a word and enable children to read. |

Taonga tuku iho |

Something handed down, a cultural property or heritage. |

Text |

Texts are constructed from one or more of the modes of meaning (oral language, written language, audio, gestural, spatial and visual modes). They are a language event that we require language skills to understand. Creators construct texts to convey meaning to an audience. For example, a speech, poem, poster, video clip, advertisement. |

Text type |

A particular kind of text with features and conventions linked to its purpose. For example, oral texts are spoken forms of communication, like speeches and conversations, while written texts are conveyed through writing, such as books and articles. Digital texts, created and accessed using technology, often include interactive elements like audio and video. |

Text creator |

An individual or group who creates texts in any mode and using any technology. |

Think-alouds |

A teaching strategy where teachers verbalise their thought processes. |

Transcription |

Describes the act of converting spoken language into written form on the page or screen. |

Trigraph |

A cluster of three letters that collectively produce a specific single sound. It can be composed entirely of consonants or vowels, or it can be a mix of both. For example, sigh, catch |

Unconstrained knowledge and skills |

“Unconstrained meaning-making knowledge and skills are learned across a lifetime and are broad in scope.” - Scott P. (2005). Reinterpreting the Development of Reading Skills. Reading Research Quarterly, 40/2, 184-202 |

Unstressed syllable |

The part of the word that doesn't receive emphasis or stress. |

Vowel |

Words are built from letters which are either vowels or consonants. Vowels are A, E, I, O, U and sometimes Y. All syllables include vowels. |

Vowel team |

A spelling pattern where two or more letters are used to represent a single vowel sound. This includes vowel digraphs but also combinations of two or more letters (e.g., -igh for /ī/). |

Worked examples |

A teaching strategy that provides students with step-by-step demonstrations or examples of how to solve a problem or complete a task. |